By Lillian Goodwin

With the COVID-19 pandemic resulting in such far-reaching panic, it’s easy to lose sight of the science among the noise. The sheer volume of COVID-19 related news is overwhelming, and it can be difficult to comb through, even with all this new free time.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided public access to their database of pandemic research, but if, for whatever reason, you don’t want to wade through dozens of dry medical journals for relevant information, this article provides a brief overview.

Foremost, the actual name of the virus causing the pandemic is not COVID-19. In order to avoid confusion, the World Health Organization mandated that media stick with an abbreviation- 2019 Corona virus disease, or COVID-19 for short.

According to the press release, there were concerns that the virus’s real name, SARS-Cov-2, might have been confused with its similar but less deadly cousin, SARS, which ravaged parts of Asia in 2003. In epidemiological terms, COVID-19 describes the disease that the virus causes, and SARS-Cov-2 describes the “agent,” or actual virus.

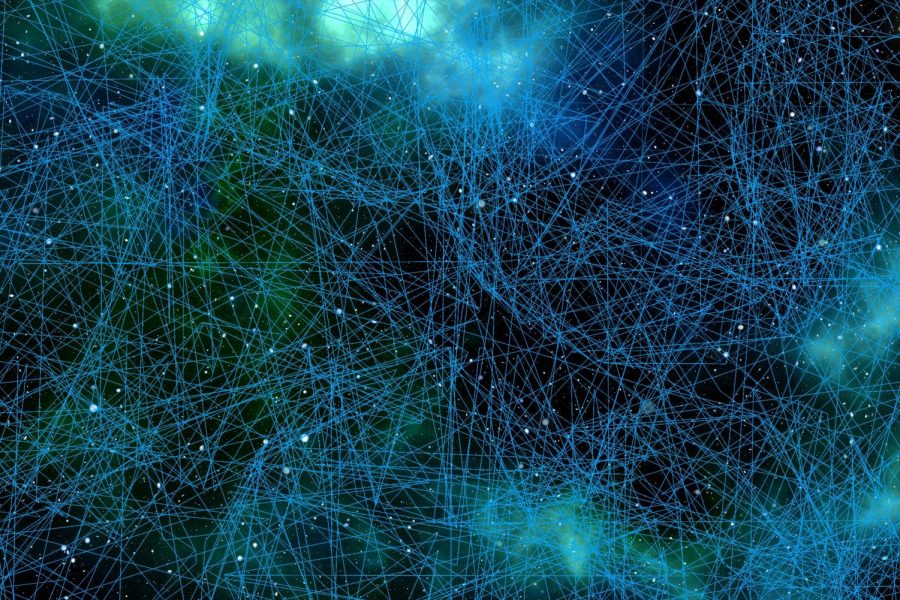

SARS-Cov-2, or “The Coronavirus” as it’s often referred to in press, belongs to the Coronaviridnae family, the largest known enveloped retroviruses. In layman’s terms, the virus is made up of a bundle of RNA, surrounded by a protective barrier. These kinds of viruses tend to be harder to develop a vaccine for and more difficult for the body’s immune system to fight off, respectively, according to literature review in Physician’s Weekly. SARS-Cov-2 is one of the seven coronavirus strains known to affect humans, next to SARS and MERS. Many strains only affect certain mammals, and sequencing by Hong Kong University suggested it’s likely a combination of bat coronavirus and an unknown strain.

Coronaviruses, like all viruses, survive by hijacking the cells of its host. Once a virus has control, it uses the cell’s machinery to make a set of virus proteins from its unique genetic sequence, which typically stops the cell from functioning properly and helps the virus copy itself. The 29 identified SARS-Cov-2 virus proteins carry out a variety of specific actions, from NSP1, which slows down the cell’s natural production, to NSP10, which hides the virus from the body’s immune system responses.

One of the more essential proteins, and part of the reason this particular strain of Coronavirus is so dangerous, is its Spike protein, or S protein, which is responsible for the virus’s entry into a cell. Coronaviridnae are identified by the unique arrangement of spike proteins on their shell, in a formation of three points resembling a crown;– hence the ‘corona’ designation, which is the Latin word for ‘crown’.

Like all enveloped viruses, they need to “fuse” their barrier with the cell’s own in order to get their genetic material inside, and thanks to a mutation in the Spike protein, the SARS-Cov-2 virus is able to do this “exceptionally,” especially to the ACE2 cells found in human respiratory systems, says the American Society for Microbiology.

Once the virus has a high viral load — or enough copies of itself inside the body — the symptoms may begin to worsen, and the individual becomes more likely to infect others with the disease. According to emergent research by University of Toronto, high viral load may also be correlated with “cytokine storms,” an often-fatal response by the immune system. In these reactions, the body overproduces immune cells, leading to lung complications, organ shutdown, or other severe side-effects. It’s the suspected culprit behind most COVID-19 related deaths, similar to the Spanish Flu and some newer influenza strains.

Because the virus is so new, much of the information surrounding its virology (how likely it is to affect people, and how severe it can get) is still being disputed. It’s still unknown exactly how infectious it is at the time of writing this, and the figures vary across institutions. The reproduction number, or the estimate of how many infections are caused by a single carrier, is far from agreed upon; The World Health Organization gave a range of 1.5-2.4, but Hong Kong University says it may go as high as 6.

Regardless, no matter how much is discovered about COVID-19, it’s likely that the mantra will remain unchanged: stay home, social distance, and practice proper hygiene.